Proving Pythagoras' Theorem with Similar Triangles

(Disclaimer: This is not a rigorous or detailed proof, I am only trying to provide a simple explanation.)

My favorite proof of Pythagoras’ familiar theorem (\(a^2 + b^2 = c^2\)) is based on similar triangles.

To prove this statement, we first have to define similarity:

Triangles \(ABC\) and \(DEF\) are similar (denoted \(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle DEF\)) iff \(\angle A = \angle D \land \angle B = \angle E \land \angle C = \angle F\).

In other words, two triangles are similar when their corresponding angles are equal.

Notice that the order of vertices of each triangle is important: \(ABC\), \(BCA\) and \(ACB\) are all different triangles in the context of similarity.

Similar trangles exhibit an important property that relates the lengths of their sides:

\[\triangle ABC \sim \triangle DEF \iff \frac{AB}{DE} = \frac{BC}{EF} = \frac{CA}{FD}\]That is, the ratios of the lengths of corresponding sides of similar triangles are equal. For the sake of completeness, I have included a proof of this statement below.

Proof

The proof of this statement depends on Euclid's fifth axiom, which is more simply stated as Playfair's Postulate:

Given a line and a point not on the line, there is exactly one parallel to the given line through the point.

We start by assuming that two triangles \(ABC\) and \(DEF\) are similar. If they are congruent, the ratios of corresponding sides are all 1 and we are done.

We will assume without loss of generality that segment \(DE\) is shorter than segment \(AB\).

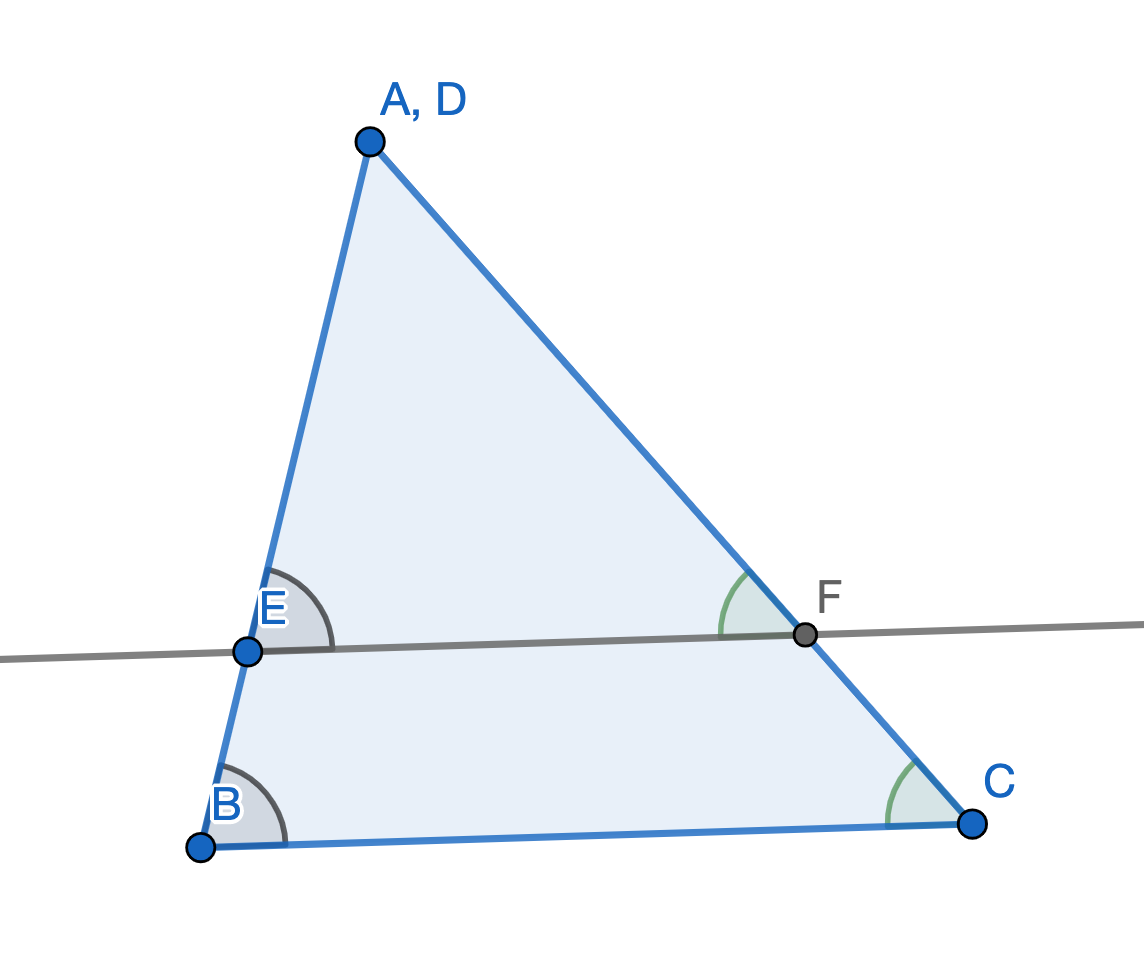

We can place \(DEF\) atop \(ABC\) such that \(D\) lies on \(A\), \(E\) lies on segment \(AB\) and \(F\) lies on segment \(CA\).

Euclid's fifth axiom and the fact that \(\angle FEB + \angle ABC = 180^{\circ}\) imply that \(EF\) and \(BC\) are parallel.

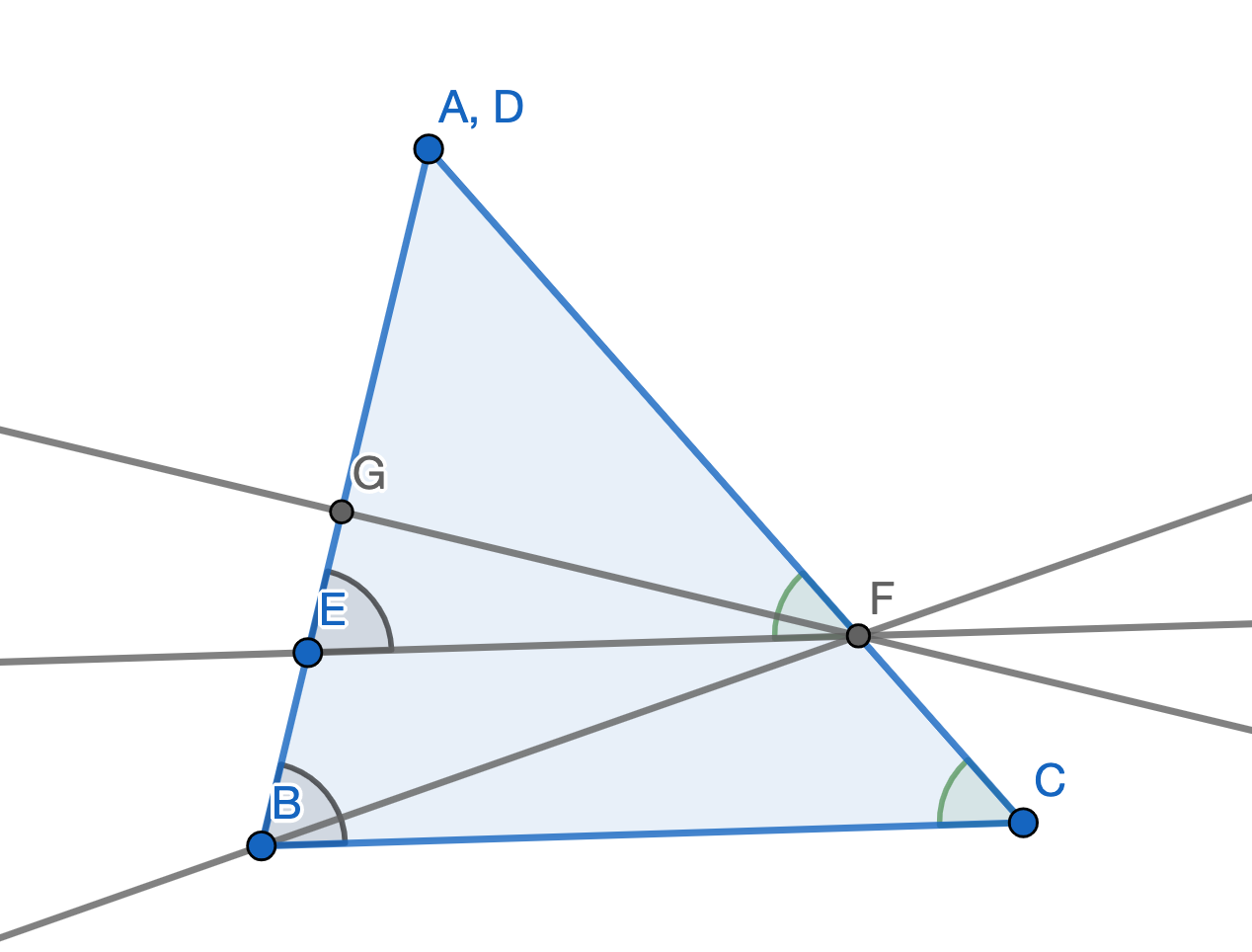

We will connect points \(B\) and \(F\) and construct a perpendicular to \(AB\) from \(F\) intersecting at point \(G\):

Now we consider the areas of \(\triangle BFE\) and \(\triangle AFE\):

$$ \frac{Area(BFE)}{Area(AFE)} = \frac{(\frac{1}{2})(FG)(BE)}{(\frac{1}{2})(FG)(AE)} = \frac{BE}{AE} $$By a similar process (drawing a perpendicular from \(E\) to \(CA\)) we can show that:

$$ \frac{Area(CFE)}{Area(AFE)} = \frac{CF}{AF} $$Since triangles \(BFE\) and \(CFE\) share base \(FE\) and have the same height (perpendicular to \(FE\)), we have:

$$ \frac{Area(CFE)}{Area(AFE)} = \frac{Area(BFE)}{Area(AFE)} $$Which implies:

$$ \frac{BE}{AE} = \frac{CF}{AF} \implies \frac{AE}{AB} = \frac{AF}{AC} $$This completes the proof of the forward implication.

To prove the bidirectional implication, we start with the assumption that the ratios of corresponding sides of \(ABC\) and \(DEF\) are equal. If they are congruent, their corresponding angles are equal and we are done.

We will assume without loss of generality that segment \(DE\) is shorter than segment \(AB\). This means that \(FD\) is shorter than \(CA\), and \(EF\) is shorter than \(BC\).

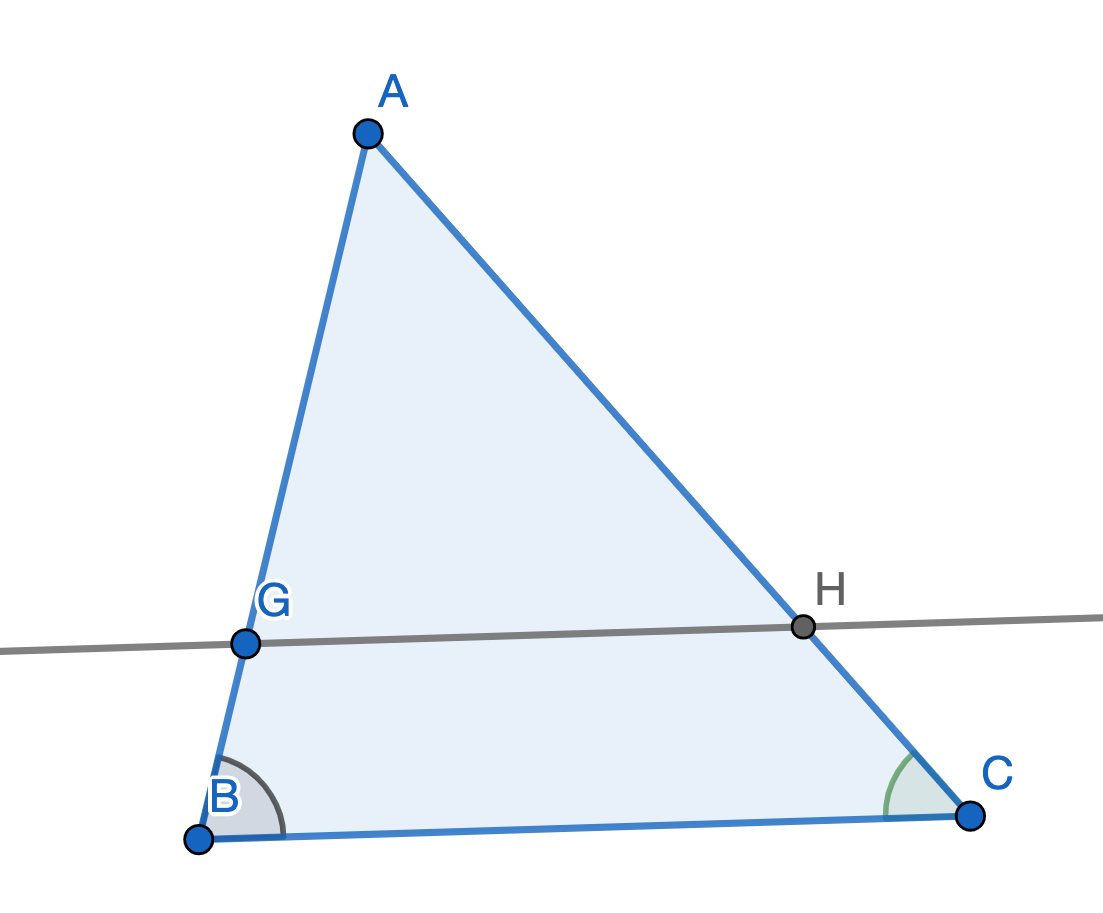

We can place a point \(G\) on \(AB\) such that \(AG = DE\) and a point \(H\) on \(CA\) such that \(HA = FD\).

We have:

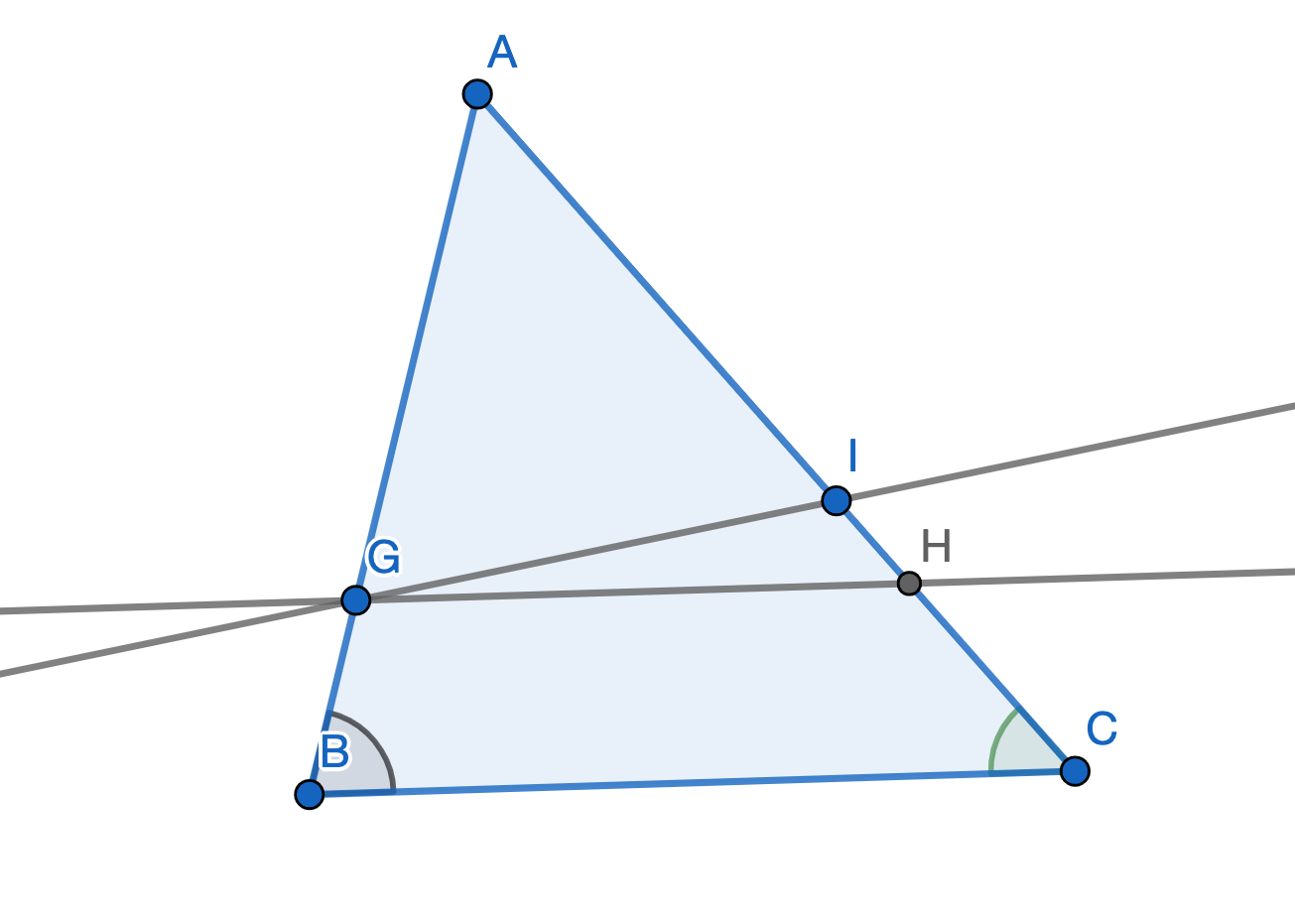

$$ \frac{AB}{AG} = \frac{CA}{HA} $$By Playfair's Postulate, there is a unique parallel \(m\) to \(BC\) through \(G\). Since \(m\) is parallel to \(BC\) and intersects \(AB\), it must intersect \(CA\) at some point \(I\).

However, as shown in the proof of the forward implication:

$$ m \parallel BC \implies \frac{AB}{AG} = \frac{CA}{IA} \implies \frac{CA}{HA} = \frac{CA}{IA} \implies HA = IA $$Therefore, \(H\) and \(I\) are the same point, and \(GH\) is the parallel to \(BC\) through \(G\).

$$ GH \parallel BC \implies \angle AGH = \angle ABC \land \angle GHA = \angle BCA \implies \triangle AGH \sim \triangle ABC $$We can now show that \(\triangle AGH \cong \triangle DEF\) by SSS:

$$ \triangle AGH \sim \triangle ABC \implies \frac{GH}{BC} = \frac{AG}{AB} = \frac{DE}{AB} = \frac{EF}{BC} \implies GH = EF \implies \triangle AGH \cong \triangle DEF $$Therefore, we have \(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle DEF\). This completes the proof. \(\square\)

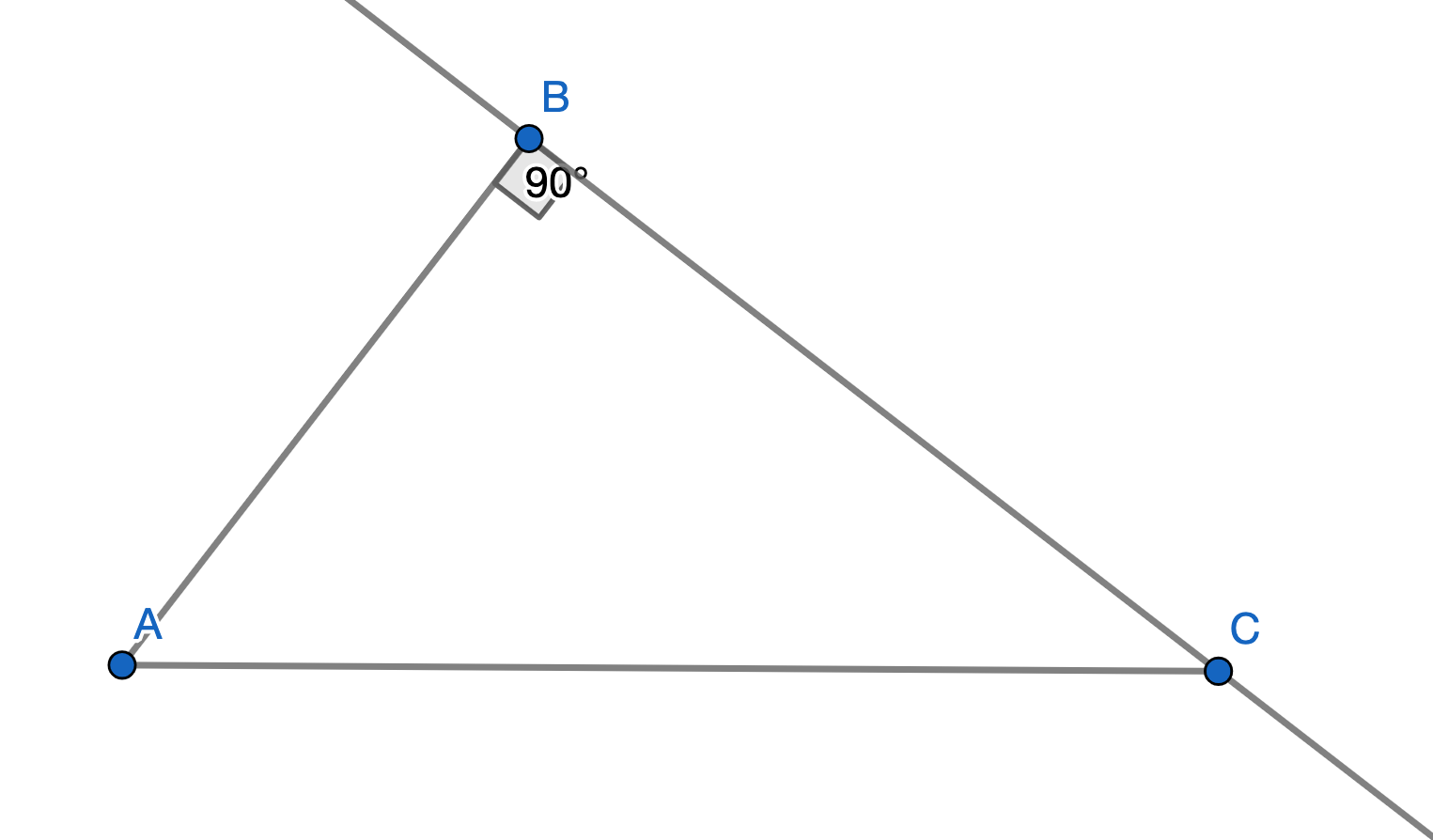

I like to think of triangle similarity as the process of ‘scaling’ a triangle up or down. For example, the triangle \(ADE\) is always similar to the triangle \(ABC\) in the following image:

Now that we have defined triangle similarity, we are ready to prove Pythagoras’ Theorem. We want to prove that \((AB)^2 + (BC)^2 = (AC)^2\).

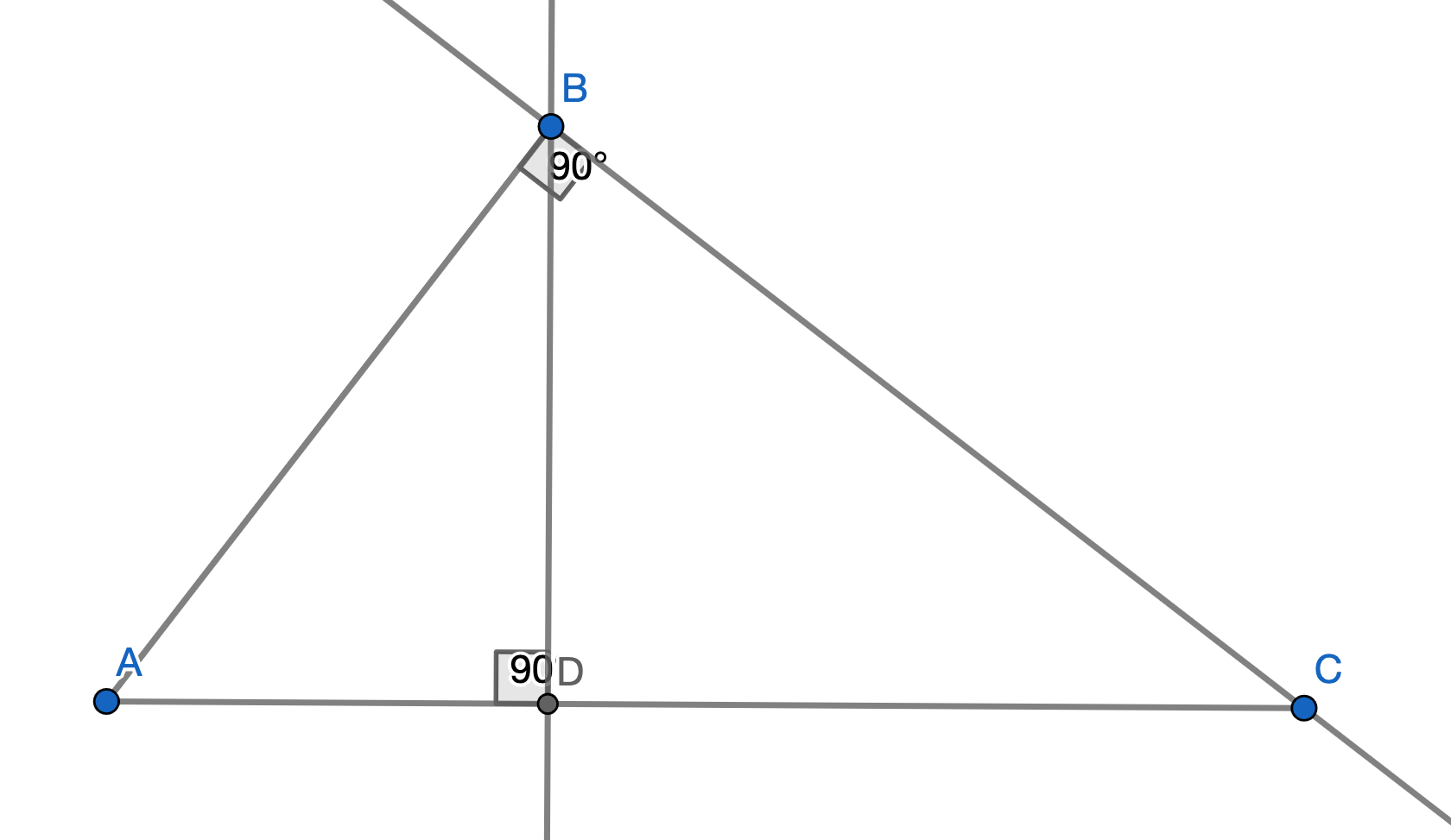

We will start by constructing a perpendicular to line \(AC\) from \(B\):

Now we will try to prove that triangles \(ADB\), \(BDC\) and \(ABC\) are all similar to each other. This is a simple exercise in applying the angle sum property – I encourage you to try it yourself.

Proof

We will first prove that \(\triangle ADB \sim \triangle ABC\). We know that the right angles are equal, and we also know that angle \(A\) is the same. By the angle sum property, the third angles (\(\angle DBA\) and \(\angle ACB\)) must be equal, so \(\triangle ADB \sim \triangle ABC\).

Similarly, we can prove that \(\triangle BDC \sim \triangle ABC\). Proving this also gives us \(\triangle BDC \sim \triangle ADB\), which completes the whole proof. \(\square\)

This gives us the following equalities:

\[\triangle ADB \sim \triangle ABC \implies \frac{AD}{AB} = \frac{AB}{AC}\] \[\triangle BDC \sim \triangle ABC \implies \frac{BC}{AC} = \frac{DC}{BC}\]We also know that \(AD + DC = AC\). All we need to do is apply some algebra:

\[\frac{AD}{AB} = \frac{AB}{AC} \implies (AB)^2 = (AD)(AC)\] \[\frac{BC}{AC} = \frac{DC}{BC} \implies (BC)^2 = (AC)(DC)\] \[(AB)^2 + (BC)^2 = (AD)(AC) + (AC)(DC) = (AC)(AD + DC) = (AC)^2\]And we’re done! \(\square\)